AUGUST '24: ON BEGININGS AND AN ABSENCE OF SWORDS

Alright, here we are, inaugural newsletter. I have clambered out of the demon pit of launch week to spew hot messy thoughts everywhere. Let’s fucking goooooooooooooooooo.

OH MY GOD I LOVED THE SUNFORGE

Thank you! I was incredibly nervous about the launch, I worried it was too ambitious, too difficult, too angry. At times while writing it felt like three books piled on top of each other. I wrote it during the first years of my transition, when I was changing but wasn’t out, and they were tremendously fraught. They were the hardest years of my life, and the book I wrote emerged covered in their stains. Women are not allowed to express anger; women have so very many reasons to be angry. I worried it had boiled up and spilled all over the pages and everybody would hate it, but it seems to have resonated deeply with its readers. The fire metaphor in the book is not subtle, fire to build and fire to burn – I worried I had set a forest fire, but it seems that I built a forge.

Also I’m sorry the shipments to A/NZ got held up so it’s not out here until September 4th.

I’M SO SORRY I HAVEN’T READ IT YET IT’S ON MY TBR

Girl it’s fine we’ve all been there. Also I mean it’s been like three weeks and I am the slowest reader, a beautiful and regal literary sloth, there’s no way I would’ve finished my own book in that timeframe.

WAIT, WHAT? I DON’T KNOW ANY OF THESE WORDS

I write books sometimes. Everybody who likes them is extremely cool. Join the cool kids’ club.

WHEN’S THE NEXT BOOK OUT

I’m about to cross the 40,000 word line on the first draft for The Worldsend. I tend to underwrite first drafts then expand them out during revisions – the first draft of The Dawnhounds was around 60k words and it ended up around 90k, the first draft of The Sunforge was around 70k and ended up around 95k. Plotwise I’m around the halfway point of my outline. I found 40–50,000 words is the tipping point where you go from running uphill to sprinting downhill and I’m looking forward to, I’ve been chunking away at this thing since around May and it’s been fun but it’s been an uphill battle and I’m ready to tear away through the second half. The first half of The Dawnhounds took me eight months to write, the second half took six weeks.

I had a lot of downtime between revisions on The Sunforge where I wasn’t really able to move ahead with book 3 because critical plot elements in book 2 weren’t locked down, and I used that time to write a completely different book. It’s a MG/YA novel tentatively called The Devil Wears White about a girl from a fantastical Aotearoa New Zealand who gets accidentally betrothed to a demon of greed, and has to break into a bank (his temple) to return the ring and annul the engagement. tl;dr Māori gal has oceangoing adventure to reach fantasy London and carry out a reverse heist. It’s currently on submission, so if the cards fall my way you might end up seeing it before The Worldsend.

Also don’t try to write two novels in one year, I’m so tired. I’m very proud of both these books and also firm in my resolve that one book a year is fine actually.

WRITE SWORDS BETTER

I intend this to be a regular part of these newsletters: I'm a writer and a fencer, and I want to bring those things together to help empower writers who DON'T fence to write swords better. If you're on my mailing list, then my experience getting bonked on the head is yours, use it as you see fit.

Okay, so:

let’s talk about sabres. A sabre is one of the most widespread types of sword, because it’s a really effective design and basically anybody who got decent at metalworking figured it out.

A sabre is any curved sword designed to be used in one hand. There are Chinese sabres, Indian sabres, African sabres. For reference, I’m trained mostly in Italian and Hungarian duelling sabre with a bit of British naval stuff thrown in there, so that’s the lens I’m operating out of. A really interesting Youtuber who specialises in African sabre (and African weapon arts more broadly) is Da’Mon Stith, I really recommend checking him out if you’re interested in that.

Sabres tend to be better at cutting and worse at thrusting. The intensity of the curve will change that balance, more curve = more cutting power. There’s something tremendously satisfying about swinging curved swords, the THWOCK THWOCK THWOCK they make, the very particular physicality of swinging something designed to be swung.

For the writer this means heaps of athletic leaping back and forth, sparks flying as swords strike each other, lots of twirling of the blade (aka a moulinet, which deserve their own whole newsletter). You know the part when the duelists lock their swords together? That’s called the bind. We’ll get more into that when we talk about rapiers and longswords, because you don’t bind with a sabre, you parry – rather than locking into the opponent’s sword you smash it away, sometimes in a shower of sparks.

Sabre duels are energetic affairs, and probably as close to the traditional image of a swashbuckling swordfight as you’re going to get. CLANG CLANG CLANG CLANG JUMP BACK, QUIP, LUNGE FORWARD, CLANG CLANG, BACK FORWARD BACK FORWARD. You want to patiently wait with your blade outstretched, ready to make the perfectly-calculated strike? Take your sensitive ass back to rapier, this is sabre, head empty nothing but parry! riposte! footwork! parry! riposte! kiss maybe!

Which is half a joke, but fencing, and sabre fencing in particular … is like … so it’s extremely physical but it also requires intellectual and emotional engagement with the opponent. It has a defined percussive rhythm that’s easy to get lost in. It releases a massive dump of neurochemicals all at once and part of getting good at it is learning to ride that wave. When somebody gets hit particularly hard we check in and we make sure to do proper aftercare. I often find myself shaking after I fence, overwhelmed by the sensation of it, just a complete sweaty mess who really needs a cuddle. This is absolutely something I want to see more writers taking advantage of, and I hope I have sufficiently communicated how.

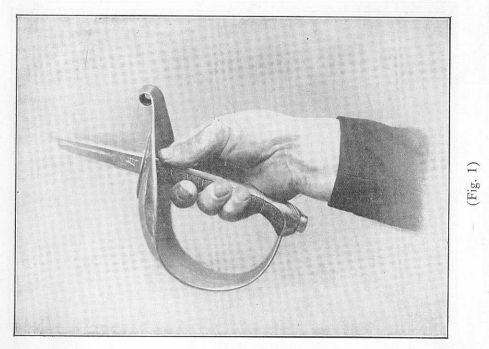

WRITE SWORDS BETTER PART DEUX: MEET JOAN

SO, this is Joan. She’s named after my grandmother, and also a jeune/jaune pun because she’s lively and spirited and golden. She’s an attempt to get as close as possible to the sort of Italian sabre that Raedelli and Barbasetti used. Late 19th century, European, designed for military use but also popular for duelling, built to be used both on foot and on horseback. I was planning to just hold her and take pictures but she’s been held up in customs, so I apologise, right now all I have is MSPaint and a photo of my girl sent to me by the blacksmith.

True Edge. The sword bit of the sword facing away from you and towards the enemy. Some sabre manuals only use the true edge to cut, and it’s generally going to be the one that’s faster and easier to attack with.

False Edge. The bit of the sword pointing towards you. Cuts with it are rare but fencers who can use it unlock some spicy surprise angles.

Point. It’s sharp and it goes into the enemy. Less commonly used to attack in sabre than in thrusting weapons like rapier but still very much a threat. This sort of Italian sabre has a relatively shallow curve, which means it cuts with a bit less verve but is more capable as a thrusting weapon.

Grip. It’s behind the guard and your hand goes on it. HOW you grip the sabre can actually say a lot about the character: if they're holding it like you'd grip a hammer they're probably untrained, or a common soldier. If they're putting their thumb on the spine (see below) they're more likely an officer or a duellist of some sort – it requires a lot more conditioning of your hands but gives you more dexterity. The cramp I had when I first started using a thumb, oh my god you have no idea. You get used to it, but it's rough at first and not where the hand naturally wants to go.

Fuller. You’ll see a lot of melodramatic language calling it !THE BLOOD GROOVE! and talking up how it does something or another with blood. This is a myth, it just makes the sword lighter. How much lighter? Not a massive amount, but we haggle endlessly over grams in this art and everything counts, especially if you’re going to have a great huge whopping heavy:

Guard. A basket (or bell) is a type of guard, which is larger, heavier, and offers a lot more hand protection. Most swords will have a guard, but it’s usually a lot less chunky than the basket characteristic of some types of sabre (and broadsword). Because of the relatively large surface area, baskets are a prime spot for fantastical decoration, and there are some very cool historical examples of this.

WHAT ELSE IS UP (NOT SWORDS)

Today, as I’m writing, it’s my first anniversary with my partner. It’s the first first anniversary of my life. It feels a bit sad to admit that at 33, but my relationships before I transitioned tended to be short and unhappy. It’s hard, if not impossible, to be honest and vulnerable when you’ve locked away such a huge part of yourself. I wasn’t even being honest with myself, I didn’t stand a chance of being honest with a partner.

So here I am, a year into a relationship, and a stable and happy one too. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a bit scared of messing it up. I’m in deeply unfamiliar waters. Still, for the first time in a long time the sky and horizon are clear.

Yours,

Alexandra ‘Sascha’ Stronach

who didn’t realise until far too late she’d made her initials ASS